When tragedies happen, we seek understanding. We want to diagnose and cure. We often try to control our surroundings and the actions of others.

We want to feel safe. It’s a basic need. That desire for security is so primal, so strong, that it can cause us to behave irrationally. I experienced this myself in my teenage years. From my softmore year in high school to my freshman year in college, I had 13 friends or mentors die. I will never forget receiving the news of the final two. I was in Austin for college when I called a friend back home in San Antonio to see about getting together on an upcoming break. She told me the news about the latest two deaths.

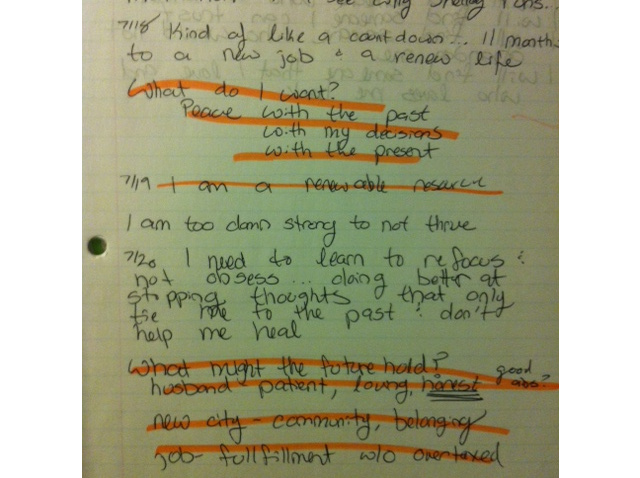

I broke. I simply couldn’t handle any more loss. My reaction? I shrunk my world. I no longer stayed in contact with high school friends. I built walls to keep out new friends. My then-boyfriend (now ex-husband) was the only one that I allowed to stay close. It worked. By shrinking my world, I eliminated the potential for hearing about or being affected by tragedy. The odds were stacked in my favor. After all, I only had one person in my inner circle.

And then there were none. My greatest fear came true; I lost him as well. Surprisingly, I was okay. I realized that my old ways of living in my walled-off world simply guaranteed less happiness at the time and yet provided no guarantee against loss in the future. I grew less afraid. More willing to take risks. I let people get close. Some have stayed, others have moved on. That’s okay. I am figuring out how to live with the natural cycles of growth and decay rather than try to fight against them.

It’s natural to examine your surroundings after a tragedy. To evaluate the weaknesses around you and to shore up any breaches in the hull. That increased security always has a tradeoff, however. It’s up to you to decide if that particular exchange is worth it.

More than a million people die in traffic accidents worldwide each year. We take precautions to keep this from happening. We gladly pay extra for cars with added safety measures, we sacrifice some comfort when we pull the seatbelt around our chests, and we write and enforce laws that limit who can drive and under what conditions they can operate a vehicle. I think we can all agree that these are reasonable measures; they balance security and freedom. Yet, how many of us look at the statistics for traffic fatalities and decide to never enter a car again? Very few. The tradeoff simply isn’t worth it.

It can be scary out there. Recent events have shown us that we cannot assume safety in our theaters, malls, or schools. There can be a temptation to scale back, pull into a shell and seal it shut. Like with me after the deaths, it does tilt the odds in your favor, but it doesn’t eliminate the risk. And, speaking from experience, life behind walls is no way to live.

Fear is an important feeling. It tells us to run when we are being chased. It tells us to seek shelter when we are under attack. It tells us to avoid high and unstable cliffs or dangerous stunts. However, fear also tells us not to love. It whispers avoidance of risk even when those chances can lead to something great. Fear tells you to hunker down and wait rather than live. Listen to your fears. But you don’t have to believe everything they say.

So continue to wear your seatbelt, but don’t neglect to drive your life.