This piece, about what happens to the people that leave relationships abruptly and/or with deception, caused quite a stir on Facebook recently. The comments fell into two camps: “Thank you for validating my experience” and “I’m the one who left my marriage and I’m tired of being painted as the bad guy.”

The reaction got me thinking about our overall views and assumptions about those that leave a relationship versus those that stay. Rarely, is it as simple as leaver = bad and left = good. Let’s explore what it means to be the one who leaves versus the one who is left behind.

The Leaver

Anyone who has chosen to end a marriage faces societal stigma. No matter how sensitively and maturely (don’t worry, we’ll talk about the jerks in a minute) they approach the divorce, they do often face the bulk of the criticism and blame. Those on the outside may paint the leaver as a quitter, not willing to put in the work to sustain a marriage. Even without any suggestion of impropriety, people may question if there was an affair that prompted the decision. Friends of both partners may empathize more with the one who has been left and put the responsibility for the pain at the feet of the leaver.

The spouse that is left may lash out in pain, a struggle to accept the situation morphing into an attack on the departing spouse. Because no matter how much the leaver tries to deliver the news with compassion, the pain screams louder than any concern. In an attempt to garner more sympathy, the left may spin stories about their ex, painting them as horrible instead of human. And for someone who struggled mightily with the decision to leave, this can be an additional punch to the gut.

It is often assumed that the decision to leave was made rashly, selfishly. Yet for the non-jerks, it may well have been an internal battle that had been tearing them up for years. And the decision may have been made as much for the well-being of the other spouse or the children as for the happiness of the one who made the decision.

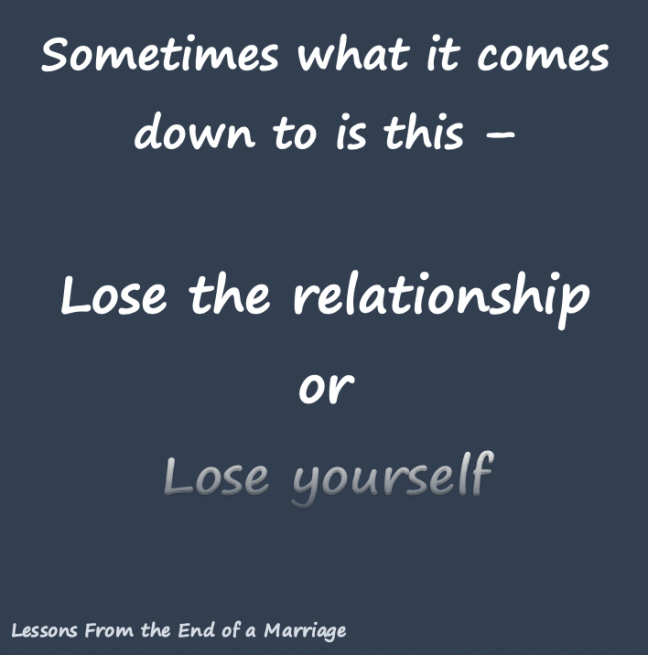

Sometimes a spouse demonstrates great courage and character by deciding to end the marriage. This is certainly the case when an abused partner gathers the conviction to leave their abuser. It is also the case where boundaries have repeatedly been ignored and promises left unfulfilled; it takes bravery to say, “Enough is enough” and be willing to walk away. And this can also be true when the marriage has real issues and the one who leaves is the only one willing to peak beneath the facade of perfection.

Those who leave are taking a blind dive into the unknown (I know some have a new bed already made; we’ll get to the jerks soon!). They are the ones making that choice and willingly accepting the repercussions. In the case of the good folks, they may agonize over the best way to announce the end so that it causes as little pain as possible.

The leaver may appear to be rational, even cold, after the news is delivered. For the non-jerks, this is usually a combination of months or years adapting to this decision and a need to start creating some emotional distance. They may be dealing with massive guilt and simply can’t bear to see the destruction of the family from the front row. The withdrawal can read as non-caring when it may simply be self-protection.

When it comes to the jerks, their motivations and approach are entirely different. They often exhibit cowardice when leaving – choosing to disappear completely, painting their unsuspecting spouse as the malicious one, embezzling marital funds to ease the transition, or cultivating an affair so that they can slide out of one bed and into another. They make no attempt to soften the blow and may even appear to revel in their ex’s pain. Their reasons for leaving are selfish in nature and may even involve years of deceptions and manipulations. Some of them are ignorant, some of them are mental ill and some of them are just assholes. And they are a big part of the reason we tend to stigmatize those that leave a marriage.

The Left

The spouse who is left usually has the benefit of society’s empathy and commiseration. We’ve all felt the pain of rejection and so it’s easy to put ourselves in that person’s shoes. Even though there still may be some judgment, usually in the form of, “What did you do to make them leave?” it is less pervasive than the criticism faced by the one who leaves.

The one who is left may be in shock and, as a result of not being prepared for this sudden change, may make decisions that seem strange or even harmful. Even though they may not face the same stigma, they may feel pummeled by a storm of the “shoulds” by well-intentioned friends and family.

Sometimes, the one who is left demonstrates perseverance and hope, aware of the issues in the marriage and determined to address them. Maybe they have sought counseling, taken the hard looks inside and made the personal changes needed to improve the marriage. When their partner throws in the towel, they may feel angry that their efforts were wasted.

Other times (like in my case), the one who is left is cowardly, afraid to see the reality of the marriage in case a mere glance is enough to shatter what remains. Maybe they are more afraid of being alone than of staying put and so they close their eyes to the facts. Or perhaps they struggle to take responsibility for their own actions (and consequences), so they stay put hoping that their spouse will be the one to take the leap (and assume the culpability).

The ones who stay may be motivated out of codependence, a belief that they can “fix” their partner. They may be willing to be a doormat, preferring to be trampled on than not needed at all. If there is abuse, they may stay because they’ve been led to believe that they “deserve” the mistreatment (abuse is never okay!) and they lack the self-worth needed to make an escape.

The one who is left may be blindsided by the split (raises hand) or may have played an active role in triaging and trying to treat the marriage. For the former, the one-sidedness of the end can not only create immense shockwaves, it can also make it harder to move out of a victim mindset. For the latter, they may feel gratitude towards their partner for taking that needed (and uncomfortable) step.

No matter the nature of the end, the way that the leaver handles it is a key factor in how the one who is left will respond. The worst ways include abandonment and character assassination. The best, a calm and in-person conversation with time to talk after the initial news has been processed. And that responsibility lies entirely with the leaver, which means the one who is left often feels powerless about the decision and the way it was handled. And this helplessness is perhaps the worst part of being left.

(I’m not going to get into the myriad effects of being left by a jerk here; I feel like I’ve addressed that enough over the years!)

Divorce isn’t easy for anyone, whether you were the one who decided the marriage was over or you were the one who received the news. Regardless of your situation, you are responsible for your actions after the decision has been made. Strive to act with compassion and kindness towards yourself and others. Divorce is hard enough as it is, there’s no need to make it harder.